Monumentality and Counter-Monumentality: How to Redress the White Social Legacy

Written by Nathalie Beauchamps, Yale 21'

Edited by Fiona Benson, Yale 22' and Esther Reichek, Yale 23'

The monument in America represents and ideologizes; it embodies value. Cheryl I. Harris, J.D. discusses the idea of a “valued social identity” in her article “Whiteness as Property.” This social identity is undoubtedly American, but also, at a more elemental level, white. Harris also identifies social identity as property, which recognizes the intrinsic value it possesses and its material impact (1758). This essay recognizes the power that monuments hold to codify social identity in America and presents two case studies that demonstrate this power of codification. The first case study looks at the National Statuary Hall Collection in the U.S. Capitol, a collection of one hundred statues donated by all fifty states, among which several Confederate historical figures are commemorated. The commemoration is a “prize” that provides a social safety net for white Americans; they do not suffer any loss of social capital for their violent past. The second case study looks at the recently changed namesake of Calhoun College at Yale University (after the famous slave apologist, John C. Calhoun), along with the physical depictions of slavery displayed throughout the building. While the National Statuary Hall still commemorates the Confederate figures, donated by several states to the collection, the counter-monumentality movements that recently took place within Yale communities led the name change of Calhoun College and the replacement of its offensive displays of slavery. Due to the success of the counter-monumentality movements at Yale, this essay will utilize the case of Calhoun College to demonstrate how exclusive monumentality can be remedied.

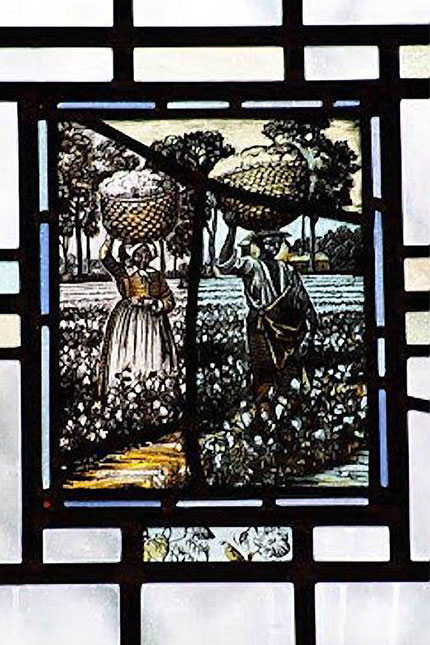

The de-contextualization of violent history within monumentality often leaves little room for non-academic communities to locate the harmful effects of such representation. Thus, little public dialogue reprimands the National Statuary Hall for celebrating an oppressively white historical memory. However, the fight to correct the monumentation of American history undoubtedly exists. It occurs most notably on college campuses and is largely grassroots. Examples of this activism include the 2017 protests at Yale to rename Calhoun College, the tearing down of Silent Sam statue in North Carolina in 2018, and the renaming of Carr Hall to Classroom Hall at Duke University in 2018 (Meiners). Counter-monumentality movements against Calhoun College reached their peak in 2016 after a Yale dining hall worker smashed a stained-glass windowpane that portrayed plantation slaves contentedly working (Remnick).

The symbolic power of monumentality should not be depreciated. Monuments symbolize, represent, and, oftentimes, commemorate. The monuments discussed in this essay are not only public displays of exclusionary whiteness, but celebrations of what it means to be American. Matthew Mace Barbee writes within Race and Masculinity in Southern Memory: History of Richmond, Virginia’s Monument Avenue that monuments “both reflect and define cultural citizenship and community belonging by enshrining in stone a community’s ideals regarding race, gender, class, and regional identity…” (Lusky, 189). A monument has the role of forging public memory and evoking particular emotions from said public (Winbery). Thus, in their shaping of public memory, the National Statuary Hall Collection and the namesake and depictions at Calhoun College make it easier to accept the memorialization of violent white Americans. They admit or ignore the racism intrinsic to their violence and accept the primacy of white accomplishments––especially racist accomplishments––over the achievements of Black Americans. As Frank B. Wilderson III mentions in his critique, “Red White and Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms,” it is almost impossible to reconcile the “unbridgeable gap between Black being and Human life” in American art (Wilderson, 57). The too often outcome of prestigious institutions––whether they be the Capitol or an Ivy League––publicly denies the existence of the Black American as a free man or even as an indignant slave. The two cases studied in this essay are hopeless in recognizing the Black individual or in hindering the perennial “tragic history and bleak future of a group of people marked by slavery” (59)...