A Revised Narrative of Objects: Sterling Library’s 1945 Gifts of Yale Association of Japan and Asakawa Kan’ichi’s Compromised Vision of an Asian Museum

Written by Isabella Yang, Yale 21'

Edited By Lica Porcile, Yale 21'

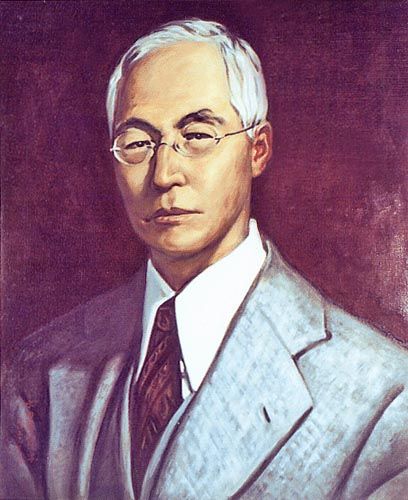

Tucked in the corner of a mezzanine-level bookshelf in Sterling Library’s East Asia Reading Room is an aged book with dark covers; on its spine are printed the simple words “Gifts of Yale Association of Japan.”[i] A reader flipping through its pages will soon recognize the majority of its contents as object accession numbers carefully laid out on the pages next to each other, followed by descriptive texts. On the inner cover are the words “Prepared by K. Asakawa, 1945.” This is the official catalog, a “self-published typescript volume,”[ii] of the 1935 Yale Association of Japan gift, known today as the Beinecke’s YAJ Collection, compiled by Kan’ichi Asakawa, one of the first people of East Asian descent to receive a Ph.D. from Yale and one of Yale’s first Asian faculty members.[iii] In 1945, Asakawa was still the leading scholar of Japanese Studies at Yale, and this compiled volume provides detailed information on each object and displays Asakawa’s ostensible effort to rearrange the collection’s taxonomy; the document was presumably a public document intended for the entire university community to read and research on.

This catalog, as well as the back story of the YAJ gift, is closely related to two other primary sources in Yale’s possession: a letter sent to Asakawa in 1934 from Ōkubo Toshitake, a notable alum who was then a Japanese senator as well as president of Yale Association in Japan (also known for being the son of one of the founders of modern Japan), and another catalog from 1935 named Nihon Bunka Zuroku (Illustrated Catalog of Japanese Culture).[iv] The former provides a context for the gift’s arrival as well as its general contents, and the latter is an illustrated catalog of representative objects in the gift compiled by the Association. While all three documents describe the gift extensively, Asakawa’s catalog, written ten years after the gift’s arrival, contains valuable information on changes over time, on both the gift sender’s and recipient’s sides. One striking discovery in the “general comments” section is that the big 1935 gift was not the YAJ’s last contribution to Yale, for new gifts continued to be made throughout the next decade and were added to this catalog: for instance, Asakawa noted that through Ōkubo’s efforts a reproduced copy of famous Japanese medieval politician Fujiwara no Michinaga’s diary, the Mido Kwan-paku Ki, was added to the collection.[v]

This is remarkable as 1935-1945 marks the most severe deterioration in US-Japan relations, and the continuous gift-making effort of Japan’s Yale-educated elites could indicate a persisting interest in amending deteriorating national relations via cultural exchange.

Asakawa, being a Japanese American caught in the tensions of World War II, was already growing increasing weary of foreign affairs. However, there was one project he had been carrying on for over two decades, which in his opinion would help to establish a proper understanding of Japanese, and in general East Asian, culture among the Yale audience: the building of a “Classical and Oriental Museum...”